Our average lifespan seems to have peaked out and even shrunk a bit recently, according to a recent survey. Scientists are scrambling to figure out why this is the case. Mainstream medical views are severely limited about potential causes. Not to worry – there’s still plenty you can do to blow the curve.

Our average lifespan seems to have peaked out and even shrunk a bit recently, according to a recent survey. Scientists are scrambling to figure out why this is the case. Mainstream medical views are severely limited about potential causes. Not to worry – there’s still plenty you can do to blow the curve.

BEFORE READING ON … ARE YOU, LIKE ME, A SENIOR WHO’S INTERESTED IN STAYING HEALTHY FOR YEARS TO COME? IF SO, YOU MIGHT LIKE TO SEE WHAT A SCIENTIST (ME) HAS TO SAY ABOUT HOW TO ACHIEVE IT AT NO EXTRA COST TO YOU, WITHOUT EVEN HAVING TO LEAVE HOME, STARTING HERE: HEALTHY AGING NATURALLY.

Now back to the feature article …

Continuing Changes in Life Expectancy

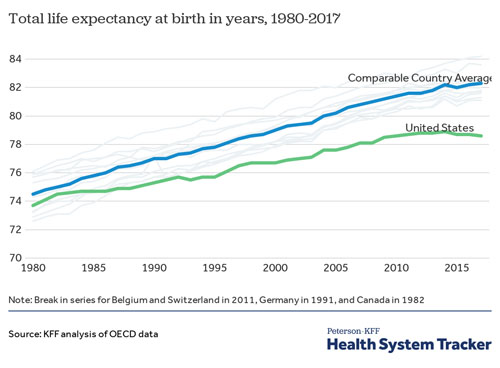

Ah, fun with statistics. Regardless of what numbers we are looking at, or how they are presented, life expectancy is a moving target. Nevertheless, for the better part of the past century, life expectancies in the U.S. have been going up. As of 2016, data for this general trend show an expected lifespan (male and female, all races) of 47.3 years for those born in 1900, increasing to 78.6 years for newborns in 2016.

That seems to be good news. However, a small dip in life expectancy has appeared more recently, at least in the U.S. And it doesn’t compare well with what we see in other developed countries.

Of course, we have a tremendously diverse population. Not just ethnically. Also socially and economically. Now everything is also colored through the filter of a COVID-19 pandemic.

If we look at the latest survey data with all that in mind, answering the question of whether our average lifespan is spiraling downward is clearly: it depends.

This article goes into some detail about just whose life expectancy is dropping and whose isn’t:

Andrasfay T and Goldman N. 2021. Reductions in 2020 US life expectancy due to COVID-19 and the disproportionate impact on the Black and Latino populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 118(5): e2014746118.

The graphs and tables can be overwhelming. The simplest view of the results may be just from the abstract of that article, as follows (note my bolding):

COVID-19 has resulted in a staggering death toll in the US: over 215,000 by mid-October 2020, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Black and Latino Americans have experienced a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, reflecting persistent structural inequalities that increase risk of exposure to COVID-19 and mortality risk for those infected. We estimate life expectancy at birth and at age 65 for 2020, for the total US population and by race and ethnicity, using four scenarios of deaths – one in which the COVID-19 pandemic had not occurred and three including COVID-19 mortality projections produced by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Our medium estimate indicates a reduction in US life expectancy at birth of 1.13 years to 77.48 years, lower than any year since 2003. We also project a 0.87-year reduction in life expectancy at age 65. The Black and Latino populations are estimated to experience declines in life expectancy at birth of 2.10 and 3.05 years, respectively, both of which are several times the 0.68-year reduction for whites. These projections imply an increase of nearly 40% in the Black-white life expectancy gap, from 3.6 to over five years, thereby eliminating progress made in reducing this differential since 2006. Latinos, who have consistently experienced lower mortality than whites (a phenomenon known as the Latino or Hispanic paradox), would see their more than three-year survival advantage reduced to less than one year.

Scientists generally attribute these differences to socioeconomic issues. Taken together with ethnic differences, what we have here is a failure to provide a reasonable causality.

In other words, surveys don’t offer any direction for how to boost individual life expectancy. Ethnicity is unchangeable. Socioeconomic factors are nearly so for most people.

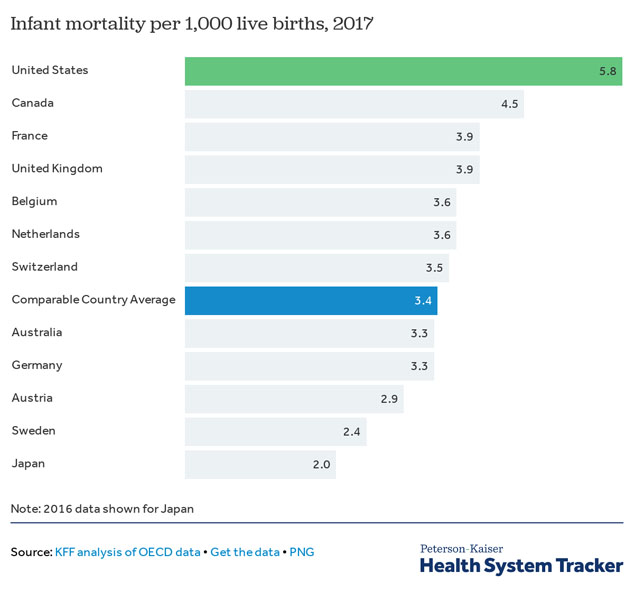

By the way, the old-time claim by our nanny state to take care of us from cradle to grave doesn’t look so good on the other end, either. Survey data also point to the comparatively poor track record we have in the U.S. for infant mortality.

What this comparison means is that we have challenges in the U.S., from beginning to end, which are greater than what we see in other developed countries.

What can we make of the latest statistics? And, more importantly, what can we do about them as individuals?

Answering those questions is a challenge all by itself. These kinds of surveys often go into excruciating detail, accompanied by some phenomenal mental gymnastics. for explaining what’s behind the statistics. As you might imagine, it’s a lot of arm-waving.

Basic Premises

Nailing down cause and effect is the most difficult thing to do in scientific studies. On top of that, surveys are correlations, which can never show cause and effect unless by implication. This is what all surveys of mortality and life expectancy share, regardless of age.

For individuals like you and me, though, this information is nearly useless for understanding what we can do about our own lifespan. Correlative statistics and putative explanations behind them are simply academic, not practical.

What’s Missing?

The biggest flaw in just about every explanation is the complete absence of anything to do with basic human biology.

A more specific and useful line of questioning has to include diving into how lifestyle choices impact how our bodies work. Instead of blaming race, social status, or income level, we should be looking at what we do to undermine our own health.

And what we do in that regard is plenty.

Fortunately for us seniors, everything we do to ruin our health can be undone. The trick is to know exactly what the health consequences are of poor vs. good lifestyle choices. This is where we are mostly on our own, since medical professionals typically give out advice that’s either superficial or just plain bad.

If you’ve had a typical Medicare physical lately, you know what I mean.

My first one, for example, entailed a lab test with a less than informative lipid profile – i.e., cholesterol and triglycerides. My total cholesterol came out at about 185 mg/dL, which is perfect. (The recommended range is 100-199.) Nevertheless, I got a call from the doctor’s office that I should eat more fruits and veggies to bring that number down. What a crock!

In addition, my vitamin D level, measured as 25-hydroxy vitamin D, was on the low end at 37.7 ng/mL. (The target range is 32-100). The advice I got was to take 1,000 IU of vitamin D3 daily to bring that up. No mention of getting more sunshine on my skin, which is the ONLY way to boost vitamin D3 levels based on actual human biology. (In fact, I’ve now built up my vitamin D level to just over 50 ng/mL exclusively by getting UVB light on my skin. Still a ways to go – and it continues to rise as I spend more time in the sun.)

I’m sure you’ve had similar experiences. Maybe you’ve even walked out of a physical exam with a brand new drug prescription. After all, the we seniors are already on an average of five prescription drugs.

The point of all this is: Mother Nature is on the back burner, basically an afterthought in modern medicine.

Your Task: Take Control of Your Own Healthspan

Increasing your lifespan isn’t really valuable all by itself. What’s most important in considering what to do about boosting longevity is ensuring good health while doing it. Nobody wants an extra few years of life if their health is dropping off a cliff. At least, I think so. Life extension by itself is not sufficient.

What we really want is a greater healthspan. In other words, a longer lifespan in good health.

This entails making the right lifestyle choices that reflect how humans evolved and adapted to life on Earth. It means taking advantage of our own biology, as it was established in Paleolithic times. In other words, living more like our caveman/cavewoman ancestors.

We have the advantage in 2021 of all kinds of modern lifestyle choices that our ancestors didn’t have. Combining the best choices with your prehistoric biology is a slam dunk for a better healthspan.

The key is finding out what those good choices are vs. the bad choices that take you down the wrong road healthwise.

It’s all up to you.

Of course, this means finding good information amongst an overwhelming amount of information and disinformation about health.

I might be biased about how and where to get started i.e., right here at the Boomer Health Center. My little introductory essay on the homepage gives you some good direction.

See what you think.

All the best in natural health,

![]()

Statements on this page have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. Information here is not is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

Leave a Reply